Sapling started when I heard about a movement, led by local Wurundjeri people, to save a tree that was growing in the forecourt of a petrol station in Bulleen in eastern Melbourne.

To me, this tree is the most perfect metaphor. It is nature’s artwork yet is stands within the most artificial landscape imaginable. It has this extraordinary value and while some people recognise that and are willing to stand up for it, to others it is nothing more than an impediment to progress. All the while the tree sits there, quietly processing a small portion of the pollution that surrounds it into the oxygen we require to live.

Around this time, I became aware of the work of Robin Wall Kimmerer. She is an American Potawatomi woman, botanist, and pioneer of the integration of traditional ecological knowledge with western academic scholarship. Kimmerer has this very interesting understanding of plants, and this opened my eyes to the sorts of relationships that we can have with them.

I had heard of the idea of giving personhood to plants to help save our forests, especially our old growth forests but her approach gave this sense of them being much more alive and with agency and their own relationships. This idea of ‘personhood’ is quite an interesting one. It is certainly not perfect, given that it still prioritises the ‘person’ part, but it has an established history that makes it useful. We grant personhood to companies, which gives these artificial organisations certain legal rights and protections. If we give this status to trees it would help to establish their rights under our existing legal system, and hopefully give them greater protection. Ironically, this is still mostly for our benefit: we cannot survive without plants but, they will thrive without us.

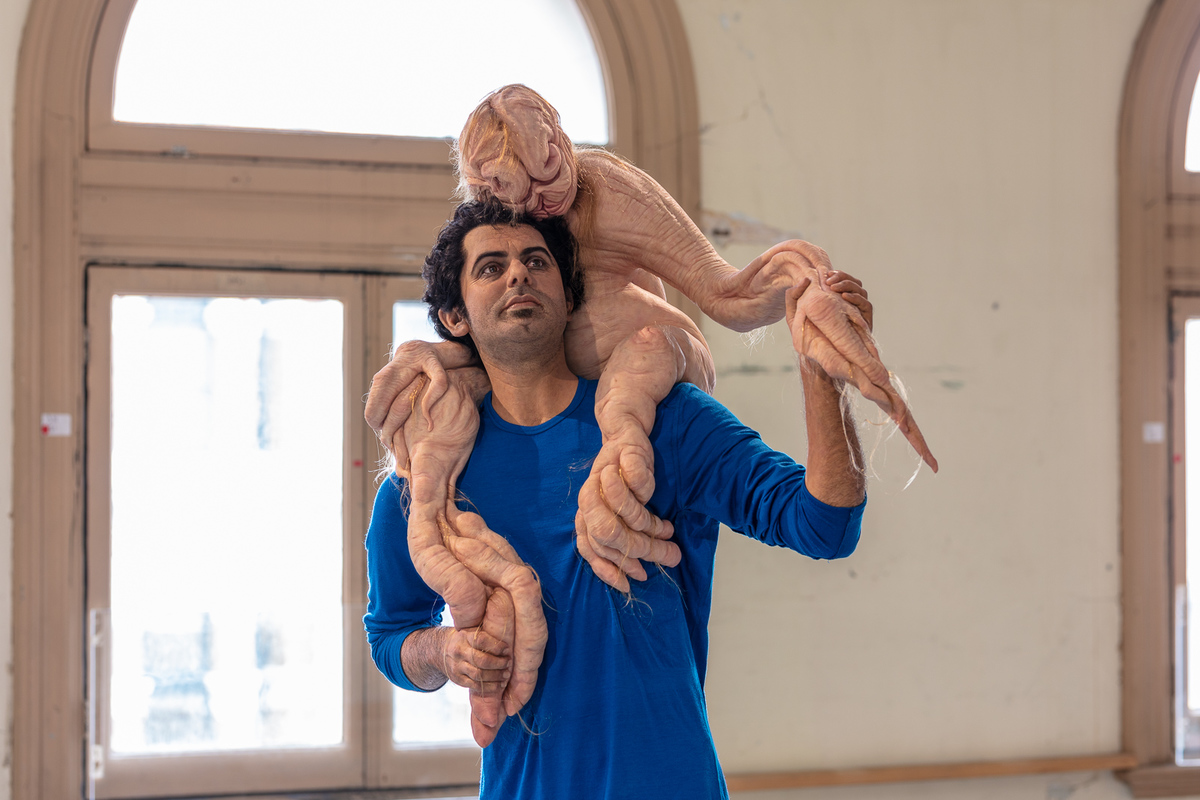

This led me to think about a work that might imagine a relationship between a person and a plant. But a plant represented with the sort of agency and sentience that allows us to see its connection to us, rather than its difference. I wanted to see the person as a nurturer of the plants rather than just seeing trees and plants as resources to be exploited for our benefit. I wanted to show the life in the plant creature. To me, even though there is an element of strangeness that comes from rendering them as this fleshy hybrid, there is also a sense of its sentience and vitality.

|

|---|

| Margit Chianelli, with a Lumholtz tree kangaroo that she had fostered. |

| Djirrbal/Ngadjonji Country, Atherton Tablelands, Far North Queensland. |

The pose is inspired by a woman named Margit who fosters orphaned tree kangaroos. In her I saw a deep and sincere inter-species relationship with a wild animal, who she supported without any desire to domesticate. The tree kangaroos would ride around on Margit’s shoulder, almost like a second head. I visited her house with Dennis Daniel, who has worked in the studio with me for more than twenty years. Dennis had children around about the same time I did, and I thought it would be interesting to present a paternal image for a change. So, Dennis agreed to step out from behind the scenes and model for the work.

|

|---|

| Dennis Daniel, with another tree kangaroo. |

Sapling is ultimately a very positive work. It presents a deeply hybrid relationship between a person and a plant/animal chimera whose personhood is self-evident despite their difference. The positivity in the work derives from our ability, or perhaps willingness, to imagine the commonality and embrace the difference of the two figures. It is not a representation of how the world is, but it is a somewhat mythological depiction of how we could connect with the organisms that surround and support us.